When Flat Justice was just getting going, back in the Summer of 2018, we quickly realised Rent Repayment Order (RRO) judgments at the First-tier Tribunal Property Chamber (Residential Property) (FtT) were not respecting the new regime of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 (HaPA). They were happily using old law in the guise of the Parker v Waller [2012] UKUT 301 (LC) authority, established under the Housing Act 2004 (HA), which gave Tribunals wide discretion in the awards they made.

We argued in our hearings that the HaPA no longer directed awards for RROs to be “such [an] amount as seems reasonable in the circumstances”, as had the HA at section 74(5) and which was used as the justification for this discretion.

When we made this case at our second hearing, Judge Latham retorted angrily:

“Are you asking the Tribunal to be unreasonable?!”

The award in that case was cut to 20% of the rent applied for. That was apparently “reasonable in the circumstances”.

We wrote to the president of the FtT in London setting out our concerns about these ‘legacy issues’ on 1st March 2019 and continued to repeat these arguments through all our subsequent cases.

Fast forward to July 2020 and we have the Vadamalayan v Stewart [2020] UKUT 0183 ruling, ironically not one of our cases: although we must have been the first to use the authority as it was published 17th July on the day we had a remote RRO hearing and managed to bring it to the attention of the rather bemused Tribunal panel.

Vadamalayan, of course, confirmed all we had been arguing for and more. The carte blanche excuse for deductions of “reasonable in the circumstances” was dead. A new chapter in RROs had dawned…or so we thought.

But, like Trump-inspired tax dodgers, some Tribunal panels have since found loopholes in Vadamalayan allowing them to ignore the spirit of this very clear ruling and to continue to slash RRO awards. Instead of relying on s74(5) of HA, they use the deductions allowable under s44(4) of HaPA for which there has been little guidance as to the extent of deductions permitted. These rulings cock a snook at the Upper Tribunal, bypassing Vadamalayan. They continue to let criminal landlords off the hook and cheat tenants of rent which should be rightfully repaid to them.

Here are some recent examples, in no particular order:

- MAN/00BY/HMF/2020/0015 (9th September 2020)

Tribunal chair: Judge Rimmer

Maximum rent repayable, confirmed by the Tribunal: £6475.00

Amount awarded: £1079.17 (a share of 25%)

Justification:

- LON/OOAH/HMG/2020/0004

Tribunal chair: Judge Prof. Abbey

Maximum rent repayable, confirmed by the Tribunal: £23,819.98

Amount awarded: £11,909.99 (50%)

Justification:

- LON/00AC/HMF/2019/0068V:CVP (11th September 2020)

Tribunal chair: Judge Korn

Maximum rent repayable, confirmed by the Tribunal: £20,917.44

Amount awarded: £9,412.85 (45%)

Justification:

- CHI/00HB/HMF/2020/0018 (30/9/2020)

Tribunal chair: Judge Lederman

Maximum rent repayable, confirmed by the Tribunal: 5,223.05

Amount awarded: 2,611.52 (50%)

Justification:

NB: the Respondent landlord in this case provided no evidence for their financial circumstances other than their oral testimony at the hearing. Indeed the R had been barred from proceedings as they had not complied with any of the directions…but were then permitted to take part in the hearing at the last minute.

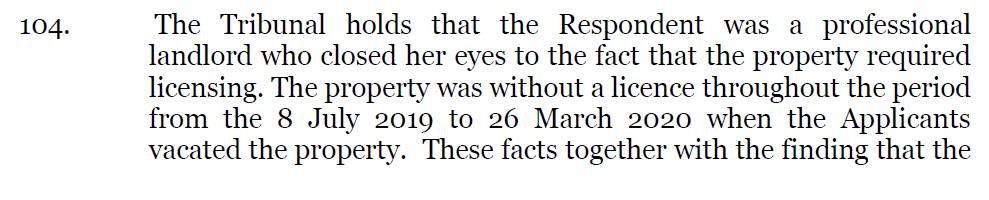

- CHI/00HB/HSD/2020/0002 (1st September 2020)

Tribunal chair: Judge Tildesley OBE

Maximum rent repayable, confirmed by the Tribunal: £19,803.00

Amount awarded: £10,000

Justification:

Discussion

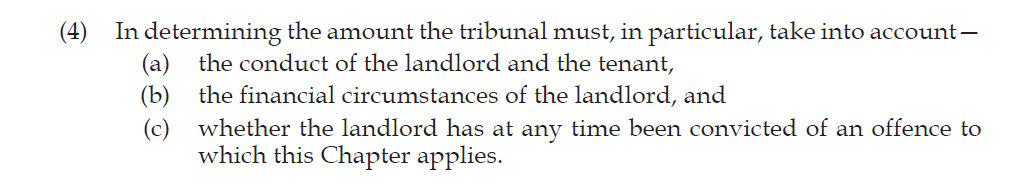

These five cases, across three regional Tribunals, were all decided in September 2020 well after the Vadamalayan ruling. Four of the decisions even discuss the implications of Vadamalayan before proceeding to make the deductions. Section 44(4) of the HaPA, which post-Vadamalayan can be the only basis for deductions, states:

These five cases, across three regional Tribunals, were all decided in September 2020 well after the Vadamalayan ruling. Four of the decisions even discuss the implications of Vadamalayan before proceeding to make the deductions. Section 44(4) of the HaPA, which post-Vadamalayan can be the only basis for deductions, states:

In the above cases there had been no convictions of the landlords so only (a) and (b) applied: the deductions all hinged on conduct and/or the landlord’s financial circumstances.

Taking financial circumstances first, it would be understandable to allow a deduction if the landlord should be in real financial difficulty. However, the Respondent should then be held to provide proper evidence of this. Simply oral evidence at a hearing cannot be enough. Even Parker ruled that such evidence must be presented in a concrete form that was open to be challenged by the As, at §40:

“the tenants would be entitled to know the facts that had led me to do so [i.e. make a reduction], not simply so that they understood the reasons for my decision but so that they could consider whether to seek permission to appeal against it.”

This is as logical and fair just as much as it is regularly ignored by the FtT. Sometimes landlords provide a typewritten, even handwritten, version of their accounts as their “evidence”; or a letter from a friendly accountant; or they just relate their tale of pecuniary woe at the hearing. This is not proper evidence. If landlords are to have deductions made from the award they must be required to supply their most recent tax returns and real proof of expenditure. After all, Rs are attempting to take away from the Applicants the rent which the latter have already proved is rightfully theirs “beyond all reasonable doubt”.

On conduct, Parker is also still relevant. Again, perfectly logically, Parker ruled that only conduct which was relevant to the alleged offence could be accounted for in the making of a RRO award. In that case, at §39, Judge Bartlett ruled that a landlord should not be punished “for matters that form no part of the offence”. Similarly, we see no reason why a tenant should be punished, through a deduction from a RRO award, for matters such as rent arrears which have absolutely nothing to do with the landlord’s failure to license. Indeed, unpaid rent cannot be applied for by the Applicants, so that the landlord wins both ways: a reduction in the RRO award for the rent arrears and the prospect of recovering the unpaid rent through court action (that rent then no longer being recoverable through a RRO).

It is worrying that all the above decisions were made within the space of just one month. Clearly, further guidance is required from the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) to support the Vadamalayan ruling and Flat Justice is committed to appealing any judgment which appears unreasonable in the circumstances.

Guy references the case above heard by Judge Robert Latham where the tenants involved received a measly 20% of the maximum rent repayable. I was one of the two tenants who applied for that RRO and was both confused and angered by Judge Latham’s incomprehensible decision. As far as I’m concerned, a landlord who is breaking the law by running an illegal HMO is guilty by default. The onus of getting licensed falls upon the landlord and it is his responsibility to get his paperwork in order. The landlord’s financial circumstances or the conduct of the tenant(s) is irrelevant here and should not be a factor when calculating an award. If a doctor without credentials operated on a patient, would it be reasonable to blame the patient for a botched operation? Likewise, if a pilot is flying a plane without a license, and the plane crashes, are we to blame the passengers for the catastrophe? Of course not. If a landlord is not licensed, he is guilty. End of story. It was unbelievable that the Tribunal should hand down such a paltry 20% of the maximum rent repayable and the GUILTY landlord get off virtually scot free. The decision made no sense to me. It was unfair and biased. Something definitely needs to change. Tenants do the community a service by bringing rogue landlords and their dodgy properties to the attention of the authorities, so they should be rewarded with the full award if the landlord is running an unlicensed business. Anything less is an insult and makes a mockery of the legal system.

How many of the Tribunal panel members are landlords themselves?

I think we can agree that judges and Tribunal members, along with MP’s, are part of a land-owning class that have a vested interest in looking after their own and ensuring the status quo of the System. You might think that the land-owning class were being generous when they enacted the Housing Act of 2016 and introduced Rent Repayment Orders(RROs) to penalise landlords managing or letting unlicensed properties. Vulnerable tenants, many of whom were living in dangerous and squalid conditions, suddenly had the law on their side and took advantage of the new legislation by taking their rogue landlords to a Tribunal. These tenants must have been so hopeful. Not only could they bring their corrupt landlords to book, but also get a year’s rent back, which, in some cases, amounted to thousands of pounds. How disappointing, then, when the judge handed down his paltry award and the criminal landlords were free to walk, laughing as they went.(I read that in one case a tenant was awarded a laughable £1!) So what goes on here? Why were RROs introduced if they don’t have any real teeth to bite? The answer, I think, is that RROs were brought in under the 2016 Housing Act purely as a SYMBOLIC gesture. The Establishment, made up of politicians, judges, and “Tribunal members”, realised that there was a crisis in the private housing sector and poor tenants were getting angry. Wanting to appease this growing discontent so that their rents would not be threatened, the Establishment passed the Housing Act and gave poor tenants what appeared on the surface to be a godsend. Tenants could now take their landlords to court. These tenants must have felt that the System really cared about them. How wrong they were. Instead of receiving the full award, they found themselves being dragged through a Kafkaesque legal system that sought to humiliate, victimise, and ultimately, blame them for crimes committed by the landlord. In some cases, it felt as if the tenant was on trial and not the landlord. Some tenants, who had very little knowledge of the law, felt intimidated and lost confidence, often being reduced to tears in the face of nasty accusations from their pugnacious landlords. What promised so much had become a nightmare. In the end, when the judge handed down his paltry award, the tenants were overjoyed that they had ‘won’. It was a relief. They were off the hook and the landlord had to pay up. For once in their life, the tenant was in the driving seat. Or so they thought. If truth be known, their ‘win’ had only been a Pyrrhic Victory. Yes, they had ‘won’, but at what cost? Had it all been worth it? Surely any fair and unbiased system would deliver a full award of 100%. But it hadn’t. In some cases the award was as low as 20% and the guilty landlord was the one who had won. He could pay the paltry fine, fix a few things in his rental property to appease the authorities, and continue as he had done before by charging exorbitant rents to financially vulnerable tenants. In spite of being fined and dragged through the courts, the landlord got off with just a slap on the wrist, while the System itself(of which he is a part) and the established order(from which he benefits) have not been affected in the slightest. Ironically, the landlords are the ones who have prospered from the introduction of an Act of Parliament that was apparently designed to protect poor tenants. ‘All that glitters is not gold’ runs the old adage. Never has this been more true when applied to the Housing Act of 2016 and its SYMBOLIC promise to equip disgruntled tenants with the ability to claim back rent using an RRO.